Reflective Statement

This year, my work has revolved around the blurred boundary between digital and physical realities. I’ve been exploring how online experiences—particularly those shaped by social media, technological absurdism, and globalised trauma—can be interpreted through audio-visual forms.

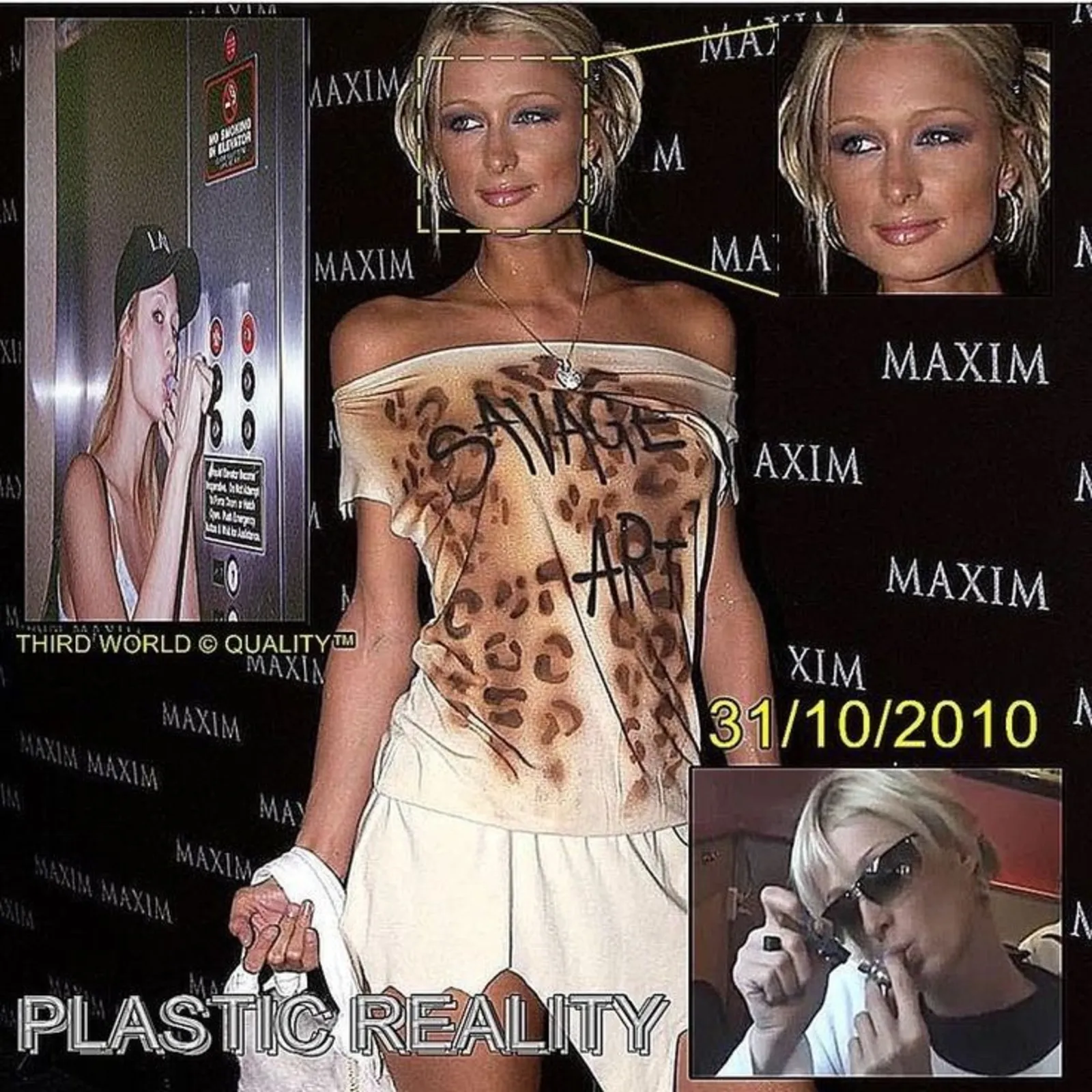

Inspired by both personal nostalgia and broader sociopolitical contexts, I became interested in the unsettling juxtaposition of war and triviality on platforms like TikTok, where a Palestinian learns English to plead for their life, while American micro-celebrities dance to Charli XCX’s new song. This contrast raises complex ethical and aesthetic questions.

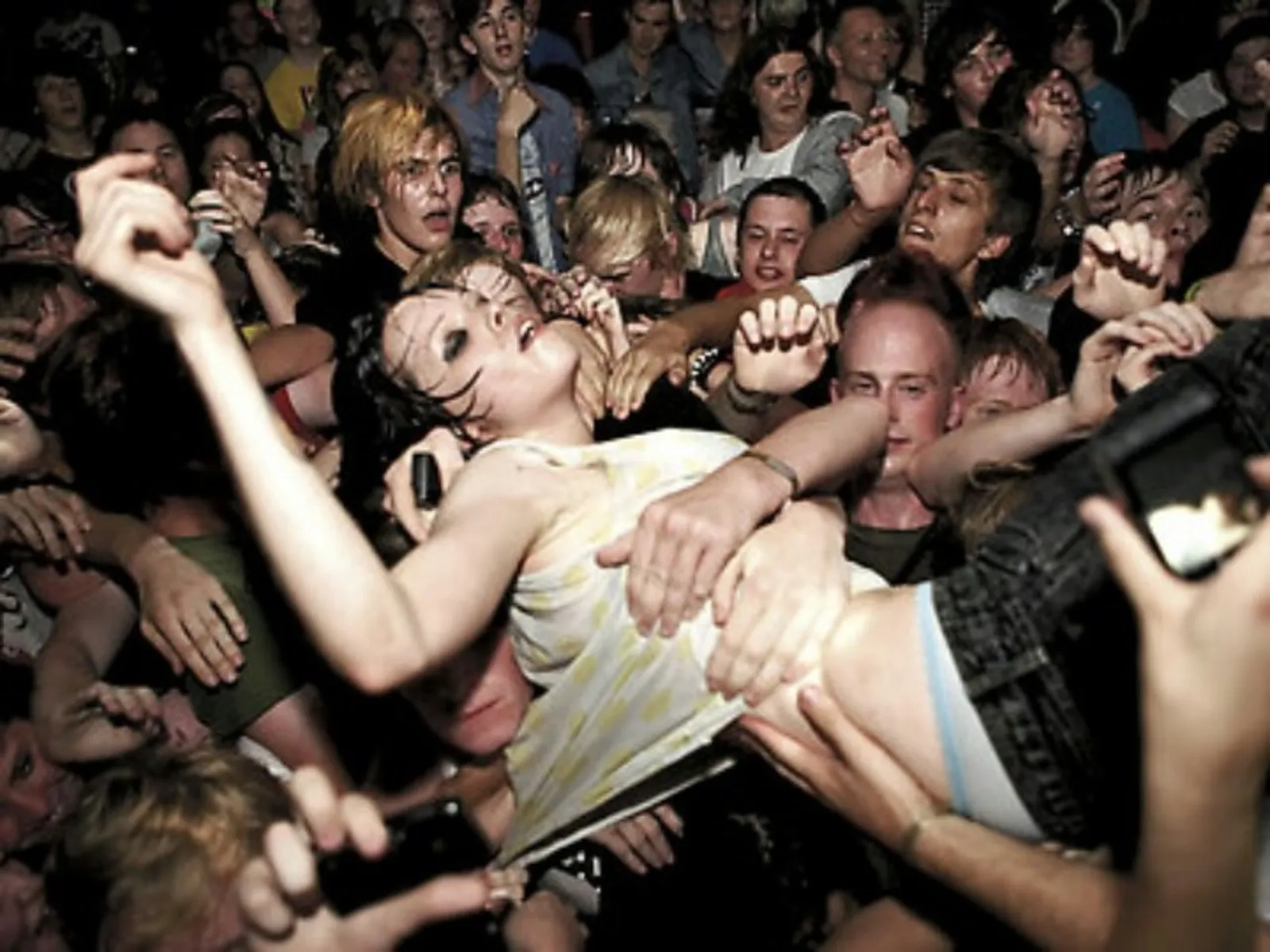

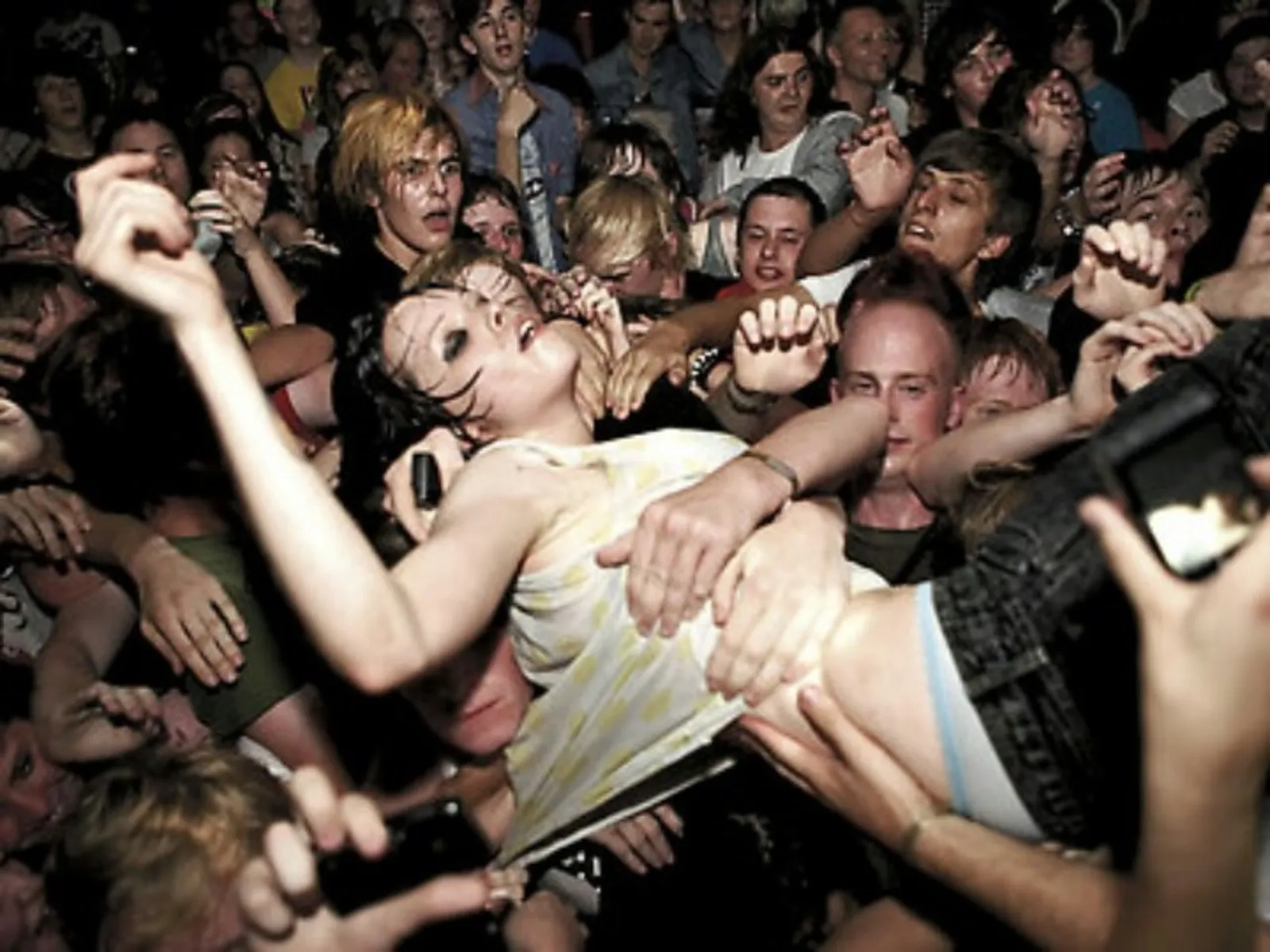

My practice has increasingly questioned how the overwhelming abundance of information reshapes our emotional responses. In the second term, my central focus shifted toward the tension between participation and spectatorship online, especially through dance as a primal, communal expression. I worked with archival internet footage, contrasting unpolished home dance videos from the early YouTube era with the highly choreographed, commercially lit dances of TikTok. This juxtaposition illuminated a shift from genuine, participatory expression to polished, performative consumption. By using dance as a universal, bodily language, I was able to bridge historical and digital contexts—highlighting how the DIY messiness and rawness of the early internet has been replaced by a more curated and aestheticised online presence. Through globalisation, this presence has become homogenised: dance trends now echo simultaneously across the world, with users replicating the same songs and movements in near-unison. There is something both fascinating and unsettling about millions of people performing the same motif, blurring individuality into a collective digital choreography.

In the first term, I explored material processes such as airbrush painting and crochet, attempting to translate online content into tangible objects. However, after attending a talk and booking a tutorial with the artist Duncan Poulton, whose insights into AI and video were invaluable, I began to question whether my work needed to leave the screen at all. He introduced me to a range of artists whose practices significantly influenced my thinking and development during this time. As a result, I shifted my focus and found that the most effective way to communicate digital themes was to remain within the digital realm. This development led me to video editing as my primary medium, and in the second term I became more interested in editing techniques, particularly rhythm and sound, rather than just content.

Recalling the “Future Shock” exhibition of digital art at 180 Strand, I began researching the software used by the artists I saw, which inspired me to progress my own technical skills. I experimented with multiple programs to deepen my understanding and ability to express digital culture through digital forms. I taught myself P5.js and TouchDesigner, building interactive works that merged code and visual output. Although I later moved away from interactivity, this period was crucial in developing my coding confidence. Continuing to refine my skills in Premiere Pro and GarageBand helped me improve both editing and audio design. Learning Adobe After Effects supported my work in projection mapping, which became essential for immersive installations.

Experimentation was vital throughout the year. I constantly installed test setups to see how the work translated off-screen. Through this, I became comfortable with AV equipment, projection mapping, and spatial planning, all of which proved essential during my degree show preparation. Experimentation became my primary research method. By testing dual screen works and projection contexts, I found what worked spatially and editorially. These trials led to significant creative decisions, such as moving away from interactivity. Initially, I was interested in interactive works that responded to the viewer’s presence or input. However, as the project evolved, I found that interactivity often disrupted the emotional pacing and immersive atmosphere I was trying to create. The piece became more about shared experience and emotional resonance than control or manipulation. By removing the need for direct interaction, I invited the viewer to engage more contemplatively, allowing the work to unfold around them rather than react to them. Another key shift was moving from a dual-screen to a single-screen format. The single screen allowed for a more focused and rhythmic edit—it felt more organic, repetitive, and intense, which aligned more closely with the emotional tone I wanted to convey.

Diana Thater’s installations allowed me to understand how to include the viewer and the body into the work on the wall. Using techniques like putting the projector on the floor helped find another way to blur the lines between the physical and the digital. In parallel with this, I took the initiative to organise AV student critique sessions, which became a formative part of my development. These meet-ups created a valuable peer-learning environment where we could troubleshoot technical issues, refine our intentions, and collectively explore how to bring our digital work into physical space. As students from different tutor groups, these sessions helped us build a shared language around digital and installation practices, fostering a stronger sense of community and collaboration.

Elizabeth Price’s work—especially The Woolworths Choir of 1979—was pivotal. Her use of archival material, rhythm, and sound helped me understand editing as not just a technical skill but an expressive language. Through researching rhythmic editing, I resonated deeply with Jacques Aumont’s quote “the ear, not the eye, is our most accurate sense organ for determining rhythm.” Similarly, Grada Kilomba’s work in Spain inspired me through her use of choral music and embodied storytelling. Her AV practice, combining voice, body, and narrative, encouraged me to incorporate sound and dance more purposefully.

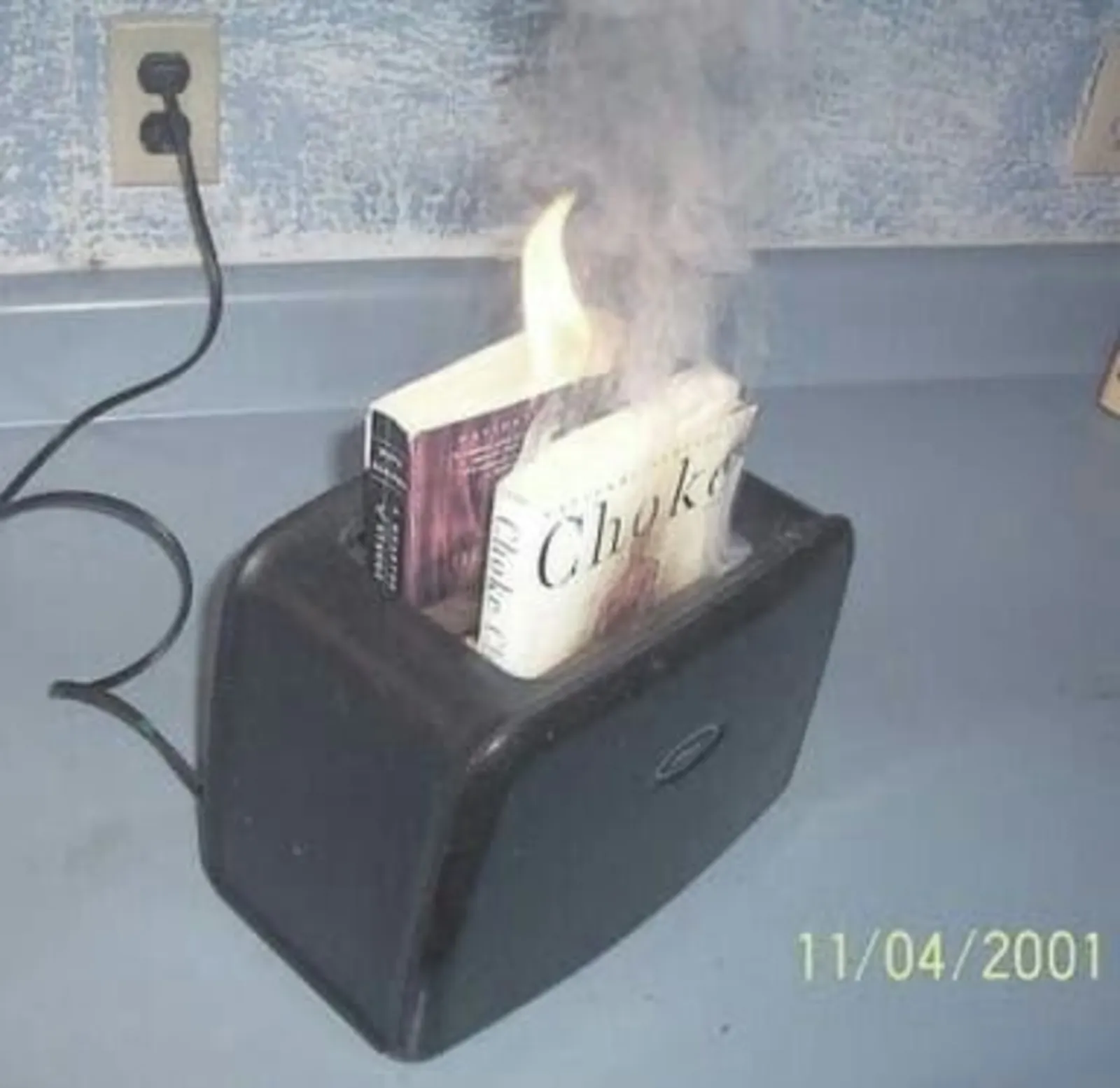

Carolee Schneemann’s radical approach to film—particularly her physical manipulation of 16mm celluloid, cutting, splicing, and layering footage by hand—deeply resonates with my own relationship to editing as a tactile, expressive process. Her work treats film not just as a vessel for images, but as a material object that can be carved, fragmented, and reassembled to communicate emotion and disruption. In the past, I experimented similarly with Super 8 film, physically cutting and looping footage using an old projector to explore rhythm and repetition. That hands-on approach taught me to think of editing not just in terms of narrative, but as a sculptural, embodied act. I’ve since transferred that sensibility into digital editing, where I continue to treat rhythm, layering, and fragmentation as core expressive tools—building emotional tone not through linear storytelling, but through pace, texture, and intuitive assembly.

Exploring the revolutionary work of Pina Bausch was instrumental to my process. Her development of Tanztheater, with its use of repeated body motifs, emotional authenticity, and emphasis on gesture over narrative, profoundly shaped how I approached movement in my final piece. Rather than focusing solely on choreography or content, I began to see editing as a choreographic act in itself: cutting, layering, and arranging footage to evoke emotional resonance. Bausch’s ability to create an emotional landscape through movement inspired me to consider how rhythm, silence, and fragmentation could be used to express internal states without relying on linear storytelling.

This engagement with Bausch's work prompted further exploration into theoretical perspectives on the body, performance, and ritual. I became interested in the body not just as a site of movement, but as a carrier of memory, culture, and spiritual meaning. I researched how dance has been used throughout history in religious and ritualistic practices—across cultures—as a form of collective experience, healing, and transformation. This understanding deepened my intention to reflect on dance as something more than performance: as a universal language that transcends time, space, and medium.

The degree show installation was the culmination of my exploration into rhythm, sound, and spatial impact. I wanted to communicate the overwhelming absurdity of the online world and reflect the sensory overload through dance—utilising editing techniques, rapid cuts, audio layering, and dual-screen presentation. By moving away from narrative content and focusing on the visceral experience of sound and rhythm, I found new ways to convey meaning. The decision to use dance and archival footage allowed for emotional resonance without exploitation. Repeated installation tests helped me refine the projection angles, audio quality, and viewer experience, ensuring that the final piece maintained the right balance between chaos and coherence.

One of the most impactful discoveries this year was the realisation that editing—especially rhythmic editing—is not just a post-production tool, but the core expressive medium of my practice. I’ve moved from making rough video collages to producing technically sophisticated pieces that consider timing, audience, and space. Over the years at university, I have been learning coding alongside my artwork, exploring creative ways to integrate the two. This dual approach has taught me how digital tools can shape not just form, but meaning—deepening my understanding of both visual language and software.

As I look ahead, I want to continue developing work in this medium, refining my approach to editing and installation while expanding my technical skillset. My interest in the intersection of art and technology has only grown stronger, and I hope to continue producing video and installation-based works that respond to digital culture—even as I enter the software engineering/technology field. I’ve been applying for apprenticeships starting in September, and I see this direction not as a departure, but as an extension of my practice. I’m excited by the possibility of building tools that could support or transform artistic production, and I hope to continue making and exhibiting work alongside my technical development. There’s still much to explore—particularly in how code, interactivity, and rhythm can merge into immersive experiences that reflect the complexity of digital life.